Jan Van Eyck (1395-1441); Northern Renaissance oil painting revolution

Jan van Eyck, portrait of a man with turban, 1433, National Gallery London.

Oil painting was among the main relevant advances in art made during the Renaissance. This new medium is documented already in the 11th century, but were the Northern Renaissance painters, among which Jan van Eyck, that at the beginning of the fifteenth century made wide use of it and spread its use in Europe.

Jan Van Eyck’s work represented the way to build paintings in the classical manner. He painted using a medium and oil colors made from scratch. The medium’s ingredients were subject to the painting stage. The medium consisted of oil, solvent, and varnish measured in specific proportions. In a strict process, he changed medium mixtures with the paint according to the rule fat over lean. Lean is a mixture of 50% oil paint 50% solvent. As he built layers, the mixture changed to a higher fat consistency by adding varnish and oil to the paint. The fat over lean process prevented cracking as the painting dried over time.

Painting techniques

In the 15th century, egg began to be replaced by walnut or linseed oil as media. These dried more slowly than tempera and created a paint that was more versatile. The use of oils and canvas supports permitted paintings to be used for a wider variety of situations, and subject matter broadened accordingly. In addition, a greater understanding of perspective and depth in the picture-plane stimulated a need for greater realism. As it was, the natural luminosity and plasticity of oil colors enabled Renaissance artists to achieve wholly new effects of color and realism, and significantly enhanced the power of their color palettes.

Following a tradition begun in Stone Age cave painting, Italian Renaissance artists employed natural chalks made from mineral pigments for drawing. Excavated from the earth, then shaped into sticks with knives, these chalks were instantly ready for use. Red chalks, with their rich, warm hue, were very popular from about 1500 to 1900, as exemplified in works by famous Old Masters like da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

Palette

Although painting techniques improved immeasurably during the Renaissance, the Renaissance palette mirrored that of the Medieval Age but for three pigments: Naples yellow, smalt and carmine lake (cochineal). Other reds were vermilion and madder lake, which brought to Europe by crusaders in the 12th century.

The Renaissance color palette also featured realgar and among the blues azurite, ultramarine and indigo. The greens were verdigris, green earth and malachite; the yellows were Naples yellow, orpiment, and lead-tin yellow. Renaissance browns were obtained from umber. Whites were lead white, gypsum and lime white, and blacks were carbon black and bone black.

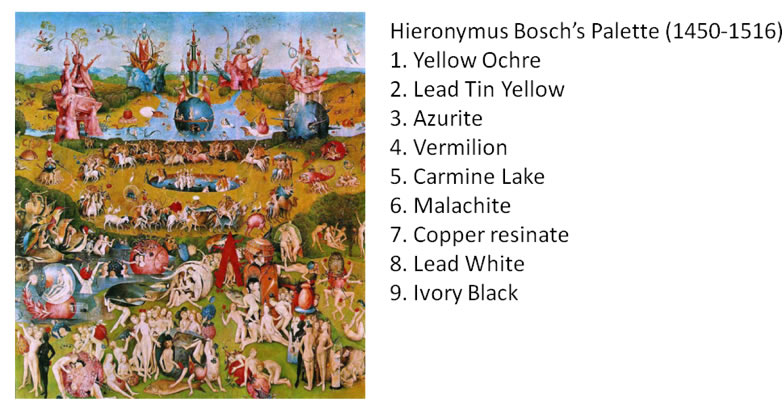

Hieronymus Bosch (1450 - 1516); late gothic palette

Hieronymus Bosch c. 1504, Garden of Earthly Delights

While his work is now categorized as Late Gothic (as opposed to the Early Renaissance work produced south of the Alps, especially in Italy), technically Hieronymus Bosch painted in a style known as alla prima, a painting technique in which pigments are laid on in one application with little or no underpainting.

However one regards 15th Century Artist Hieronymus Bosch - as subversive heretic or squeaky-clean Catholic, scientific diarist or smack-high loon - the enduring substance of his work reveals a creative, inventive, fantastical talent created during very turbulent and perplexing times.

Tintoretto (1518-1594); late Italian Renaissance palette

Tintoretto, Miracle of the slave, 1548, Gallerie dell'Accademia

Tintoretto was probably the last great painter of the Italian Renaissance and one of the greatest painters of the Venetian School. His dramatic use of perspective space and special lighting effects made him a precursor of Baroque art.

In the Miracle of the Slave, the Venetian painter Tintoretto (the son of a master dyer) used carmine pigment in order to achieve dramatic color effects. The painting forms one of the chief glories of the Venetian Academy and represents the legend of a Christian slave or captive who was to be tortured as punishment for acts of devotion to the evangelist, but was saved by the miraculous intervention of the latter, who shattered the bone-breaking and blinding implements about to be applied.

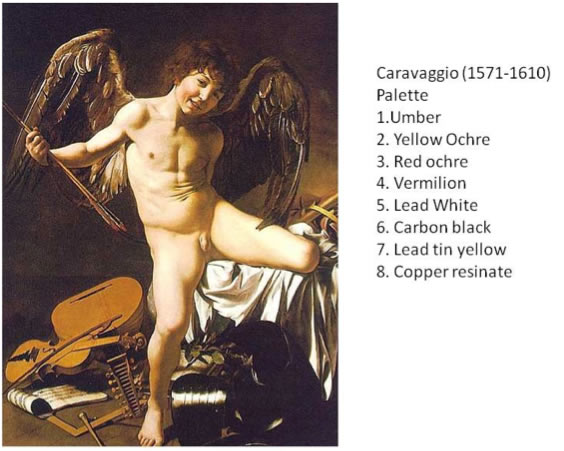

Caravaggio, the Baroque palette

Caravaggio, Amor vincit omnia, 1603, Staatliche Museen Berlin.

Caravaggio "put the oscuro (shadows) into chiaroscuro” Chiaroscuro was practiced long before he came on the scene, but it was Caravaggio who made the technique definitive, darkening the shadows and transfixing the subject in a blinding shaft of light. He achieved this effect with a limited palette: ochre (red, yellow, umber), a few mineral pigments (vermilion, lead tin yellow, lead white), organic carbon black, and copper resinate. Earths and ochre predominated, and brighter colors were always veiled.

Rembrandt (1606-1669); the Dutch Golden Age palette

Rembrandt, The Feast of Belshazzar’ c.1635, National gallery London.

Rembrandt used lead white in flesh tones, white cuffs, and collars and lead tin yellow in highlights.

Dutch vermilion, produced by the direct combination of mercury and sulfur with heat followed by sublimation, was highly developed in the time of Rembrandt. He typically preferred to use bright red ochre heightened by the addition of red lake rather than vermilion, which he used only occasionally.

The lake pigments (produced from textile dyes fixed to a precipitate formed with alum and potash or to a chalk substrate) typically used in oil painting to produce effects of richness and depth over opaque underlayers, were rarely used for this purpose by Rembrandt, who typically mixed lakes directly with other pigments to enrich their color.

Ochre’s stability, range of color, and range of translucency to opacity suited Rembrandt’s purposes well and therefore tended to predominate in most of his paintings. In addition to iron oxide, umber contains black manganese dioxide that has a siccative effect on linseed oil. Therefore, they were added by Rembrandt to the ground layers to promote faster drying.

Vandyke brown was often used by Rembrandt for his initial monochromatic sketching of a composition and for deep brown background glazes. It is a very poor dryer, hence Rembrandt always mixed it with other earth pigments to avoid this defect.

Smalt was popular because of its low cost. Its manufacture became a specialty of the Dutch and Flemish in the 17th century. Smalt is a very good dryer and was used by Rembrandt for this purpose and also to give bulk to thick glazes containing lake pigments, which are poor dryers.

Verditer, a synthetic azurite, was available in the 17th century and has been found in some of Rembrandt’s paintings. Azurite appears more frequently in Rembrandt’s early work. In the later pictures, Rembrandt used smalt for blues. Azurite is a good dryer because it contains copper that has a siccative effect on linseed oil. Rembrandt therefore often added azurite to pigments that were poor dryers.

Bone black is considered the deepest black of all and was used extensively by Rembrandt in the sketchy under layers of his paintings and for the deep black of the costumes worn by his sitters.

Rembrandt used carbon black primarily as a gray tinting pigment in the upper ground layer on his canvas paintings, which occasionally can be visible as the cool half tones in flesh areas.