Measure by measure.

While poetry is a written literary form, it derives from an oral speaking and singing tradition. Thus, most poetry is written to be read orally. A poem’s movement and core building block comes from the rhythmic measure of its line, or meter. Measured in stressed and unstressed syllables, the meter is very similar to musical time signatures. A reader can deduce pace, emotion, and the spirit of a poem from its meter.

For instance, the most common meter of classic English poetic forms, iambic pentameter, constitutes five metrical feet per line, with each metrical foot combining an unstressed and stressed syllable:

du-DUH/du-DUH/du-DUH/du-DUH/du-DUH

The BIRD/ate SLOWLY/through SEED/dropped BY/rainSTORM

The basic measurements are:

- Hexameter: six metrical feet per line

- Pentameter: five metrical feet per line

- Tetrameter: four metrical feet per line

- Trimeter: three metrical feet per line

- Dimeter: two metrical feet per line

The most common types of meter used in poetry through the ages are:

- Iambic: Unstressed syllable, followed by a stressed syllable

- Trochaic: Stressed syllable, followed by an unstressed syllable

- Anapaestic: Two unstressed syllables, followed by a stressed syllable

- Dactylic: A stressed syllable, followed by two unstressed syllables

- Spondaic: Two stressed syllables

- Paeonic: A stressed syllable, followed by three unstressed syllables

Thus, dactylic tetrameter would consist of four metrical feet of stressed syllables, followed by two unstressed syllables:

Du-DUH-DUH/du-DUH-DUH/du-DUH-DUH/du-DUH-DUH

Con-SI-DER/bats-FLY-ING/through-NIGHT-FALL/in-DARK-NESS

When scanning poetry with an ear to the meter and measure, it’s possible to immerse yourself in the music that flowed through the poet when he or she observed and composed the movement – giving you access to the richness of the poet’s inner world at the time.

Deciphering poetry.

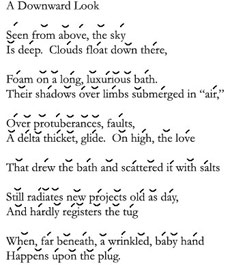

Depending upon your perspective, a line of poetry can be enlightening, entertaining…or confounding. How many times have you looked up from a poem, a haze descending over your mind, and asked yourself, "What does the poet mean?" Teachers, students, aspiring poets, and long-time readers all have experienced this conundrum, and often decided the poet was too far "out there" or that simpler poetry or literature was more to the readers’ liking.

Tools that uncover poetic diamonds.

Every line of good poetry contains its music and its treasures. As readers and interpreters of the work, we have to use the proper reading and speaking tools to uncover the diamonds hiding within the words. To start, it’s best to ask a perfunctory question: "From what within the poet or the poet’s life did the poem originate?"

A good poem arises from the confluence of four places, not unlike four rivers joining together:

Soul: When a poem arises, it feels like the bosom of the poet lifts up and births the spoken or written moment. The point of origin lies at the furthest depths of the poet, often calling into play ancestral memories, divine or universal inspiration, and insights or truths that "magically" resonate with the reader.

Mind: The intellect plays a vital part in the creation of a poem, bringing perspective, structure, and word choice to the experience conveyed on each line. Worldviews, social and cultural attitudes, depth of thought, comparison and contrast, and conclusions all inform the poet as he or she writes.

Heart: Nothing moves a poem like expressed emotion. The vast majority of poems spring from seven emotions: anger, joy, sadness, fear, courage, lust, and excitement. Word choice, pace, punctuation (or lack thereof), and meter convey the poet’s state of emotion. If transferred purely to the poem, they will likely provoke the same feeling in the reader.

Experience and Observation: A poem is a single experience or observation, distilled to a fine spirit by the poet’s life experience and refined by his or her intellect and choice of words. Every poem conveys an experience or observation of some kind. If you are familiar with this experience or have researched it, you are better able to interpret the poem.

Riding the wave.

Properly experiencing or interpreting the first line of any poem is vital to the reading or spoken-word experience. If you can’t feel the poem or see where it is heading, it becomes very difficult to understand. Like a rising wave, a good first line will provide everything you need to anticipate the ensuing experience: subject, meter, voice, emotion, energy, and structure. By reading the first line, and then identifying these aspects, you position yourself to interpret everything that is to come from both an emotional and intellectual point of view.

Look at this famous first line from Walt Whitman’s masterful 13-line poem, After The Sea-Ship:

After the sea-ship, after the whistling winds

We can draw the following inferences from this line of poetry:

- The poem will be about what happens to the sea (an actual sea, our mind, our heart) after a ship passes – literally and figuratively. The experience of a ship passing and a wind whistling are far different than what happens afterward, when an eerie calm settles in but the surrounding area or body of water still churn;

- The poem conveys tremendous emotion if taken figuratively. When a ship passes through our life during a storm (whistling winds) and then moves on – a relationship, a friend, a peak event – our emotional state tends to swoon;

- The line ends without punctuation – movement;

- The voice is clear and precise. This is an experience that will be directly conveyed;

- The poem opens on the back end of a storm, communicating great intensity and energy. We will be reading about the churning aftermath;

- Notice how Whitman uses the word "the" twice within an eight-word first line. That is highly unusual in poetry, where "the" is often avoided. These words are chosen deliberately. It could be "my" sea-ship, but it isn’t. It’s "the" sea-ship. It belongs to all of us and none of us. He has universalized the poem.

The second line further establishes where the poem is going:

After the grey-white sails taut to their spars and ropes

By feeling the experience, as well as tracking it with our minds, we can deduce from this line:

- The mariners were faced with a robust open-ocean storm;

- The crew used tremendous energy and skill to avoid capsizing;

- While "grey-white" is the color of the sails, it also reflects the color of the sky;

- Taken figuratively (all of Whitman’s poems read clearly at multiple levels), the line continues the experience of an emotional storm.

- There is no punctuation. The ocean is roiling. He makes sure that we feel it.

Now, let’s see where the first two lines take us:

Below, a myriad myriad waves hastening, lifting up their necks,

Tending in ceaseless flow toward the track of the ship,

Waves of the ocean bubbling and gurgling, blithely prying,

Waves, undulating waves, liquid, uneven, emulous waves,

Toward that whirling current, laughing and buoyant, with curves,

Where the great vessel sailing and tacking displaced the surface,

Larger and smaller waves in the spread of the ocean yearnfully flowing,

The wake of the sea-ship after she passes, flashing and frolicsome under the sun,

A motley procession with many a fleck of foam and many fragments,

Following the stately and rapid ship, in the wake following.

When reading the first line, it’s helpful to peruse the entire poem or opening stanza (if it is a lengthy poem), then return to interpret the first line.

Tools for Reading Poetry

A few simple tools can help to transform any poetry reading experience from a bout with incomprehension to an enjoyable study on the way words, lives, emotions, souls, and experiences move through the eyes, minds, and hearts of the women and men who wrote these works.

- Read more about the source of the poet’s inspiration. If you can discover what’s in the poet’s soul, heart, and mind, you can unearth his or her motivation for putting pen to paper.

- Try reading each line aloud. See if you can feel the energy and emotion as each word forms upon and releases from your lips. Pause accordingly at each punctuation mark. Take another breath. Sense the musical rhythm. Imagine the poet reading the work through your voice.

- Study the movement. What is the meter? How are punctuation marks used – if they’re used at all? How do syllables and meter work together? This movement defines the inner experience of the poem.

- Consider a poet’s word choices. Picture the nouns and try to envision yourself in that place or holding that thing. Feel the verbs and look at how they move the poem forward. Interpret how and why the poet matched nouns and verbs in such a specific way. Take these noun-verb match-ups from the opening of Gary Snyder’s poem, "High Quality Information." Watch how Snyder uses the verb-noun combination as gerund phrases to move the poem and create an economy of words, which are reflective of two of Snyder’s feeding-pool traditions, Zen and haiku. Note lines three through five:

A life spent seeking it

Like a worm in the earth,

Like a hawk. Catching threads

Sketching bones

Guessing where the road goes.

- Study the structure. Chances are, there’s a specific reason why a poet chooses a particular form to write a particular poem. If you can learn more about the form from this exhibit, the books listed in additional resources, or another source, it may be easier to interpret a poem written in that form. Then ask, Why did the poet choose that form? How does that form bring out the subject or mood of the poem? For example, a poem written in free verse conveys a more open relationship between a poet’s voice and the experience than a poem written in tightly rhyming quatrains.

- Explore additional layers. Poems are the world’s greatest extended metaphors. For countless centuries, poets were vital information links to citizens in repressed societies. If a poet didn’t write metaphorically, he or she faced the wrath of the ruling regime. Since poems draw from the souls of their authors, they usually transmit the experience at different physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual levels, creating an exciting atmosphere of discovery for the reader. When scanning a line of poetry, see how it feels. Does the line relate to your core truths and beliefs? If you feel happier or sadder – or any other emotion – after you’ve read it, you’re probably uncovering the poem’s deeper layers.

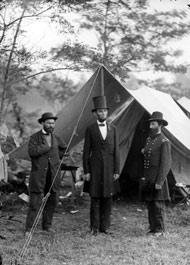

- Read from inside and outside the poet’s cultural context. One of the best ways to gain perspective on the vastness and richness of a poem, particularly a poem from yesteryear that still commands attention today, is to read from within and outside the poet’s cultural context. Learning more about a specific poet’s life, interests, home, circles of friends, and his or her social and cultural setting gives you hints so you can more clearly interpret the work. For instance, a study of Walt Whitman’s life indicates that he lived at the onset of the Industrial Age, he was an ardent naturalist and a lover of America, he believed in individual freedom of expression at all costs, and he suffered from blindness as an older man – all of which come out in the keen inner observation, wonderful tomes on nature, and alternating periods of conflict and co-existence between nature and industry in his poems. "O Captain My Captain," perhaps Whitman’s most famous poem, is a salute to a man he admired above all – Abraham Lincoln. It was written after Lincoln’s assassination.

- Don’t worry if you don’t get it. Some poetry is very dense and obscure. That’s why academics spend years analyzing poets and the meaning of their work. If you can’t get through an 18th-century sonnet without tearing your hair out, put it down and try another form. You may even find that you enjoy writing poetry more than you enjoy reading it. Why not give it a try?