The limerick’s origins.

Although no one knows for sure, the limerick form is thought to have germinated in France during the Middle Ages, after which it crossed the English Channel. An 11th century manuscript demonstrates the limerick’s cadence:

The lion is wondrous strong

And full of the wiles of wo;

And whether he pleye

Or take his preye

He cannot do but slo (slay)

The form contains five lines with trimeter (three-beat) measures in the first, second, and fifth lines and dimeter (two-beat) measures in the second and fourth. While this rhyme scheme of abccb differs from an Irish limerick, the similarity is unmistakable.

From Shakespeare to Mother Goose.

Five centuries later, William Shakespeare used the limerick’s rhythm in Stephano’s drinking song in The Tempest, as well as in Othello and King Lear. Yet it wasn’t until the early 1700s that soldiers returning from the continent-wide War of the Spanish Succession brought the limerick form to Ireland. In 1776, it appeared in published form in Mother Goose’s Melodies; 25 years later, when Mother Goose nursery rhymes attained fame, the limerick was forever affixed to children’s literature. During that time, a group of local Irish poets composed limericks during drinking sessions at various pubs – including, some say, a pub in Limerick that was already noted for its pub crawl chorus, "Will you please come up to Limerick?"

The limerick craze.

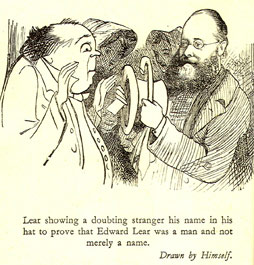

The limerick appeared throughout Irish and British literature in the mid-19th century, most notably the printing (1846) and reprinting (1863) of Edward Lear’s A Book of Nonsense, the latter celebrating Lear’s 40-plus years of writing what he called "nonsense verse." While Lear didn’t invent the form, he certainly popularized it. From that release came a magazine, Punch, that ran limerick contests and launched the limerick craze. By century’s end, poets and writers such as Alfred Lord Tennyson, Algernon Charles Swinburne, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Mark Twain experimented with and published the form. Limericks became the subjects of weekly newspaper contests, with large prizes awarded. The humor and easy creation of limericks infused oral poetry across class-lines. Wrote one critic, "It is the vehicle of cultivated, unrepressed sexual humor in the English language."

Limerick experimentation.

Like its more staid poetic cousins, the limerick has undergone experimentation and adaptation. The traditional five-line verse has been joined by such variations as the double limerick (10 lines), extended limerick (six lines), reverse limerick (replies to other limericks), beheaded limerick (nonsense verse), tongue-twisters, limeraiku (three lines, 5-7-5 syllable count), and truncated limerick (short last line).