The Rise of Renaissance Perspective

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 14. The first known diagram of the two-point perspective by Pélérin (1505), showing the pairs of vanishing points that each determine the angels of one set of parallels.

|

Raphael

was apparently emboldened by his effort to compose the only full-fledged

oblique construction of the Renaissance, the ‘Coronation of Charlemagne

by Pope Leo III’ (1519) occupying the main wall of the third Stanze.

This painting depicts the major event establishing papal power throughout

the Holy Roman Empire, whose consolidation after 700 years was being

celebrated in the Raphaelle Stanze and the Sistine Chapel being painted

by Michelangelo at the same point in time. This depiction should therefore

represent the summit of Raphael’s achievement and the most complete

expression of his technique. The drama of the moment is vividly captured

by the angled rows of cardinals, the figures reaching forward and the

marked shadows stretching across the scene. It is telling of the level

of understanding of perspectives other than the standard one-point construction,

therefore, that Raphael’s two-point composition has no unifying

perspective layout.

|

|

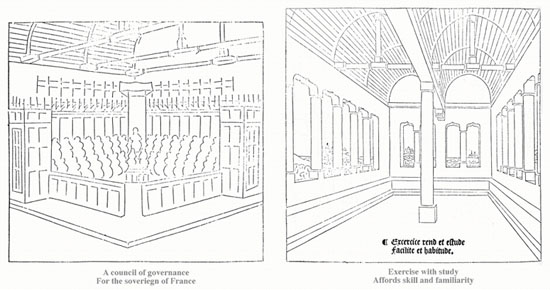

Fig. 15. Two perspective figures from

Pélérin’s ‘De Artificiali Perspectiva’

A. A rare example of an oblique perspective construction. B. A design

with a barrel vault.

|

|

In order to reconstruction the perspective,

it is necessary to ‘read’ the intended layout of the scene,

a task in which there is potential ambiguity. In view of the fact that this

is the first full attempt at a painting with angular perspective, it seems

reasonable to assume that Raphael intended a straightforward plan in which

the chamber was rectangular but was viewed from an oblique angle. Examples

of the geometry of angular perspective had recently been published in France

(in 1505) and Bavaria (in 1509) in ‘De Artificiali Perspectiva’

by Jean Pélérin (Fig. 15A). A copy of this book might well

be expected to have found its way to the premier artists at the center of

decorative excellence, the Vatican. It is not unreasonable to suppose that

Raphael would have been inspired to elaborate such a construction, implying

a rectangular underlying plan. Fig. 15B from the same book bears a strong

resemblance to the vaulted ceiling in the background of the painting, suggesting

that Raphael may have combined the two constructions to develop his elaboration.

This possibility, however, suggests the seed of his problems. While the

assembly room vault is an accurate two-point construction, Raphael’s

vault is in one-point perspective with a lateralized vanishing point. The

two constructions cannot be validly melded together if all the corners are

right angles. Strictly speaking, in fact, any shift of the principal vanishing

point away from the center implies a need for a second vanishing point to

appear one the opposite side. This is a requirement that was never accurately

met during the Italian Renaissance. Analysis of Raphael’s ‘Coronation

of Charlemagne’ provides a prime example of this lack, even if the

assumption of a rectangular plan is relaxed.

|

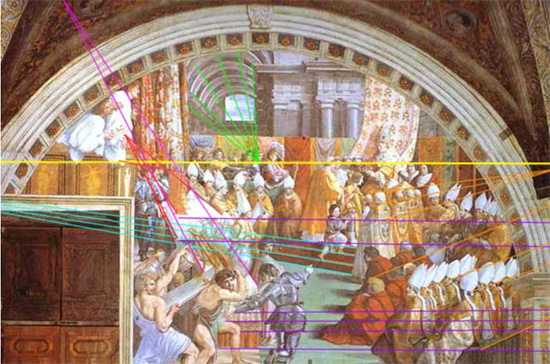

| Fig.

16. Reconstruction of the vanishing points in Raphael’s ‘Coronation

of Charlemagne’. All vanishing points should lie on the yellow

horizon line. In fact, the lines for each of the tables, the line

of votive candlesticks, and the cardinals in the right foreground

all deviate from this requirement. |

|

There are a number of obviously rectangular

objects in the painting that allow reconstruction of the vanishing points

of each set of parallel sides. The perspective rules are simple. If all

these objects are aligned with the same rectangular grid, all the edges

of the rectangular objects should converge to either one of exactly two

vanishing points. Both vanishing points should be at the intended level

of the horizon. Any deviation from this construction anywhere in the picture

implies a lack of adherence to the rectangular grid. (The more relaxed possibility

is that the objects, while still rectangular, are arranged at a variety

of angles on the grid. In this case, any number of vanishing points up to

twice the number of objects is possible, but all vanishing points should

still lie along the horizontal line of the horizon.)

The reconstruction of Fig. 16 makes it clear,

however, that Raphael adhered to neither of these rules. While each object

has a plausible vanishing point, the vanishing points neither cluster at

two locations nor lie along the same horizontal line. To complete the set,

we may assume that the oblique line of cardinals in the foreground is sufficiently

homogeneous to allow construction lines across similar joints of their bodies.

With this inclusion, we find that Raphael has used no less than 6 vanishing

points a different levels in the scene, strongly violating the requirement

that they all be at the same horizon level. Furnishings that are clearly

intended to be aligned with each other also have different vanishing points.

In total, there are eight different horizontal positions of the vanishing

points where there should be two if the whole composition was on a uniform

oblique grid. The similarity of the elements of the scene to some of the

separate illustrations from Pélérin’s book (Figs. 15A

& B) clearly suggests that Raphael adopted the particular construction

for each part of the scene without understanding how they should be modified

to form a coherent perspective projection.

The remarkable feature of angular perspective

is that, although it was well-understood by geometers such as Pélérin

(1505) and Vredemann de Vries (1605), it was avoided by virtually all artists

until the middle of the seventeenth century. Aside from two paintings of

doubtful attribution painted around 1440, the first successful use of full

angular perspective was by Dutch artist Gerard Houckgeest in 1650. (There

was limited use of the angular construction in floor tiling throughout the

period, but this could easily be achieved by connecting the corners of a

one-point perspective grid, and did not require an understanding of the

rules of two-point construction.) Inspired to develop a radical design for

his painting of the tomb of William the Silent, the king whose efforts united

Holland in 1581, Houckgeest turned to Vredemann’s architectural representation

technique of the oblique construction for the interior of the church at

Delft. This dramatic shift from the unremitting one-point perspectives of

the church interiors of Saenredam and Neeffs gained Houckgeest immense popularity

in The Netherlands, but it was to be another half-century before the two-point

construction appeared in Italy in the hands of Canaletto. The long progression

from the early perspective approximations of Cavallini and Giotto around

1300, through the one-point developments of Masolino and Mantegna in the

1420s, to the two-point sophistication of Houckgeest and Canaletto was a

span of 400 years. The intellectual endeavor of the full representation

of space was evidently no easy matter, and was largely an effort of the

artists and architects of the time.