The Rise of Renaissance Perspective

Who is represented as Aristotle? He was considered the fount of the Catholic philosophy, through Thomas Aquinas, so represents the link between Catholicism and humanism. One might therefore expect it to be a portrait of the Pope, Julius II, who had inspired the present artistic endeavors. Previously, Aristotle’s philosophy had been considered opposed to Plato’s, but the two had recently been reconciled by the classicist interests Marsilio Ficino, who translated many of Plato’s works, Bishop Nicholas de Cusa and orator Pico de Mirandola (CHECK DETAILS). Since the painting is centered on this reconciliation, one might expect one of these notable figures to be represented as Aristotle. However, neither of these proposals is plausible because all four candidates were clean-shaven whereas Aristotle has a substantial beard.

The beard provides a telling clue to the model for the Aristotle

figure. The undisputed master of the high renaissance was Titian (Tiziano

Vecellio), the pinnacle of Venetian elegance in painting. As testified by

his self-portraits, Titian sported a beard as a young man (painting ref) and

grew it progressively longer with age (multiple painting refs). Although his

dates are uncertain, Titian certainly overlapped with Raphael, is about the

only painter of his generation with a beard. In the modern assessment, he

was the undoubted heir of the Leonardesque subtlety of style in the decades

following the master’s death (1520-1550). Is it possible that Raphael

could have made this bridge?

On present scholarship, the timing is tight. The ‘School

of Athens’ is dated to 1510 and Titian’s birth estimated as 1488

- 1490. So, on this dating, he would be receiving this high accolade of the

passing of the artistic baton at the age of 22, at most. It is not impossible,

as he was a precocious artist, and received a knighthood (chevalier de l’etat?)

not long after at the age of ?32. At least ?? authorities put Titian’s

year of birth at 1477, making him 33 at the time of Raphael’s putative

portrait, which is well in accord with the youthful vigor of the portrait

of Aristotle. Who better than the author of the famous ? series of frescos

to honor as the successor of the high Renaisaance spirit?

The identity of Aristotle with Titian is supported by the comparison of Raphael’s

portrait with one of Titian’s self-portraits from about the same time

(Fig. 5). It may be seen as being overly complimentary to Titian to align

him with such overarching figures as Aristotle and Leonardo, but politics

may have played a role. There had been a long-standing tension between the

Venetian and Roman/Florentine branches of the Italian art. Placing Titian

in the role of acolyte to Leonardo’s teachings would have been a way

of emphasizing the central role of Rome in the cultural dissemination of the

Renaissance ethos to the Venetian power base.

|

|

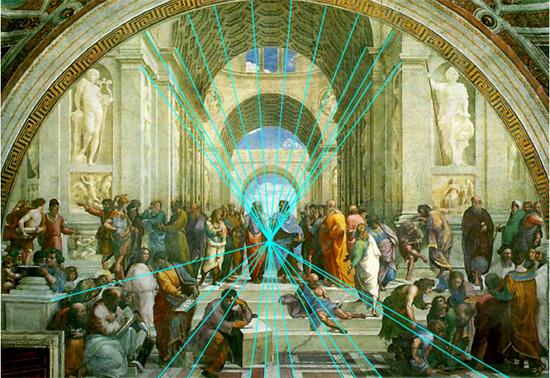

Fig. 6. Reconstruction of the central

vanishing point within the full architectural scope of Raphael’s

‘School of Athens’, which measures 8 m wide by 6 m high.

Note that the vanishing point, though accurate, does not fall on any

significant feature of the scene, such as Aristotle’s outstretched

hand nearby.

|

|

The ‘School of Athens’ has often been cited (e.g., Bärtschi,

1976; Arasse, 1978) as an example of the use of a vanishing point to emphasize

the significance of the composition. The central figures here are the aging

Plato and Aristotle as his brilliant young pupil, emphasizing a philosophical

point with his outstretched right hand. What more natural than to draw attention

to this focus by locating it at the vanishing point of the entire edifice?

The problem with this interpretation is that the vanishing point is actually

about half a metre below Aristotle’s hand (Bärtschi, 1976), as

shown in Fig. 6. However Raphael defined his geometry, the mismatch makes

it less likely that he intended the vanishing point to play the specific role

of accentuating the outstretched hand that is often attributed to it. Perhaps

he wished to draw attention to the central pair of figures, or perhaps the

idea of placing the infinite in the hand of a mere mortal was actually avoided

as being sacrilegious. The development of a concrete location for the vanishing

point was contentious in the early Renaissance because it was difficult to

conceive of infinity compressing to a point in space. There was, in fact,

no physical evidence that a point was the valid extrapolation because no lines

could extend to the physical point, even in the longest of plazas.

|

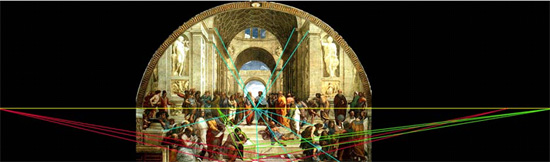

| Fig. 7. Reconstruction of the lateral

vanishing points for the School of Athens. The distance points to

either side (red lines) are reconstructed on the assumption that the

tile pattern in the foreground is based on square elements. The drafting

table in the foreground projects to a substantially smaller angle

between the vanishing point, a subtle error that nevertheless results

in the appearance that its surface is not horizontal (see Fig. 4). |

|

Returning to the actual location of the central vanishing point, we can ask

whether it allows veridical viewing of the painting’s perspective. To

do so, the viewing position has to meet two conditions. The viewer’s

eye has to be directly in front of the vanishing point, and it has to be the

correct distance away from the surface. (It should be noted that these conditions

are rarely met in practice, for any painting.) Now, Raphael’s painting

in enormous, with the inner tableau being fully 6 m high and 8 m wide, not

including the encircling frieze and arch. The bottom of the painting is 2

m above the ground and, being a fresco, its fixed position in the wall plaster

was obviously understood by the painter. The net result is that the central

vanishing point is no less than 4 m above the ground, completely inaccessible

to even the tallest human viewer, whose eye height would be unlikely to exceed

2 m. It is evident that Raphael (or Bramante) did not feel compelled to project

the perspective to a realizable viewing location.

Actually, Raphael constructed the floor with some care, given the assumption

that he constructed the perspective to be appropriate to a version of the

painting in a different setting. This accuracy can be seen from the construction

of the lateral vanishing points (or ‘distance points’) defined

by the grid of the floor tiling in the foreground. As mentioned, these lateral

vanishing points should fall on exactly the same horizon line (yellow) as

the central vanishing point. The red lines show that this conjunction with

the horizon is indeed the case for the lower tiling, the one least associated

with the ceiling vault that determines the horizon line with greatest accuracy.

Although it is a long stretch, the red lines in Fig. 7 converge convincingly

to the horizon line, which is itself on the true horizon implied (although

not actually visible) through the final archway. Were the painting to be

viewed at the correct height and viewing distance, it would have the correct

construction to evoke the maximum sense of depth. The reader may try this

out by viewing Fig. 4 with the eye directly in front of the vanishing point

at a distance equal to the width of the reproduction. For most viewers,

the perceived depth dramatically increases, and the archways appear to recede

in accurate parallel fashion. Once at the correct center of projection,

the eye is free to look around the painting in any direction without violating

the perspective fidelity. The depth impression is actually enhanced by such

movements.