Feeding creative explosions.

For many centuries, poetry movements and communities have served as the most provocative, creative, vital, engaging, and oft-underground elements of regional and national literary trends. The simple joy of gathering for a single or group reading, listening to verse, hearing background stories, and discussing poesy has joined and empowered poets from ancient Athens to the streets of San Francisco. The assemblies launched social and political discourse while feeding creative explosions that, in nearly all cases, involved the arts and music as well.

Stepping into community.

Despite the popular view of most poets as solitary, hermetic people, communities are vital to most working poets – which is why, in any given week, thousands of open-mic and guest poetry readings take place in the United States. Whether we’re studying the history of poetry or listening to an individual poet, it’s enticing to make connections between two poetic periods, or between a poet and his or her influences. In doing so, we invariably set foot inside a poetic movement or community.

Movements through history.

Throughout history, there have been hundreds of major and minor poetic movements and communities. Major community-based movements – such as the Ancient Greek poetry schools, Provencal literature, Sicilian court poets, Elizabethan and Romantic poets, American Transcendentalists, Paris expatriate (Surrealist), and Beat poets – changed the course of poetry during and after their respective eras.

Claude McKay’s book of poetry, Harlem Shadows, was among the first books published during the Harlem Renaissance. McKay was part of a literary community with widespread influence.

|

Confessionalists, such as Sylvia Plath, were a part of a tributary movement that contributed to the body of poetics.

|

Insight into ten great movements.

By taking a closer look at ten great community-based movements in Western poetry, we can glean greater insight into their genesis, their contributions to world poetry and literature, and their cultural influences.

Ancient Greek poetry (7th to 4th centuries B.C.)

The pinnacle of ancient Greek poetry lasted three centuries, making it one of the few multi-generational poetic movements and communities. Ancient Greek poets were also unique because they were the first large group to commit their poetry to writing; prior civilizations preferred the oral tradition, though some written poems date back to the 25th century B.C.

Ancient Greece’s cultural explosion ended when it was conquered first by Alexander the Great and then by Rome. The Romans borrowed from Greek works to develop their own dramatic, literary, and poetic movements. As Greek works became disseminated through the Western world, they created the basis for modern literature.

Provencal literature (11th to 13th centuries)

Like a giant iron cloud, the popes of the Holy Roman Empire – the purveyors of the Middle Ages – clamped down and extinguished creative and artistic expression. However, as the 11th century reached its midpoint, a group of troubadour musicians in southern France began to sing and write striking lyrics. They were influenced by the Arabic civilization and its leading denizens, Omar Khayyam and Rumi, inspired by Latin and Greek poets, and guided by Christian precepts. Three concepts stood above all others: the spiritualization of passion, imagery, and secret love. With a gift for rhythm, meter, and form, the musicians and poets created a masterful style by the 13th century.

The Provencal troubadours began as court singer-poets, among them William X, Duke of Aquitaine, Eleanor Aquitaine, and King Richard I of England. They practiced the art, but its undisputed masters were Bertrand de Born, Arnaud Daniel, Guillame de Machant, Christine di Pisan, and Marie de France. During their heyday, these and other poets routinely traveled to communities to deliver poems, news, songs, and dramatic sketches in their masterful lyrical styles. Among those deeply influenced were Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarch, and Geoffrey Chaucer. Forms like the sestina, rondeau, triolet, canso, and ballata originated with the Provencal poets.

The Inquisition doomed the Provencal movement in the 13th century, though a few poets continued to produce into the mid-14th century. Most troubadours fled to Spain and Italy, where two new movements flourished – including the Sicilian School.

Sicilian School (mid-13th to early 14th centuries)

Emboldened by the passionate poetics of the Provencal troubadours, a small group of Sicilian poets in the court of Frederick II turned verses of heartfelt love into the first spiritual heartbeat of the Renaissance – and the ancestral work that would explode in England during the Elizabethan and Shakespearean eras.

In the twelfth century, Sicily integrated three distinct languages and cultural influences: Arabic, Byzantine Greek, and Latin. The small society was well read in both ancient Greek and Latin, and women were viewed more kindly and tenderly than in other medieval cultures. When Sicilian poets interacted with the Provencal troubadours, they found the perfect verse form for their utterances of the heart: lyric poetry.

Beginning with Cielo of Alcamo, the court poets developed a series of lyrical styles that used standard vernacular to make art of poetry. They were aided by Frederick II, who required poets to stick to one subject: courtly love. Between 1230 and 1266, court poets wrote hundreds of love poems. They worked with a beautiful derivative of canso, the canzone, which became the most popular verse form until Giacomo de Lentini further developed it into the sonnet. Besides writing sonnets, de Lentini continuously invented new words in what became a new language – Italian. Among the best-known poets were de Lentini, Pier delle Vigne, Renaldo d'Aquino, Giacomo Pugliese, and Mazzeo Ricco.

As the 14th century dawned, the Sicilian poets’ canzones, balladas and sonnets came to the attention of Dante and Petrarch, who spread them throughout Bologna, Florence, and other emerging literary centers. By the time the Renaissance arrived, nearly 100 poets were plying their trade throughout the culturally awakening country–and scholars from England, France, Spain, and Germany were watching.

Elizabethan and Shakespearean eras

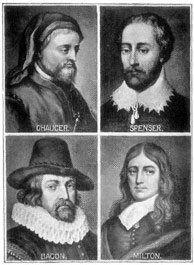

By the time the Italian Renaissance waned, its greatest poetic exports–the ballad and the sonnet–found their way to England through Sir Thomas Wyatt. He introduced the forms to a countryside attuned to lyrical and narrative poetry by the great Geoffrey Chaucer, whose experiences with latter Provencal poets influenced the style credited with modernizing English literature.

Sonnets swept through late 16th and early 17th century England, primarily through the works of Wyatt, Sir Philip Sydney, Edmund Spenser, and William Shakespeare. Spenser and Shakespeare took the Petrarchan form that Wyatt introduced to the literary landscape and added their individual touches, forming the three principal sonnet styles: Petrarchan, Spenserian, and Shakespearean. The other fixed verse influence – Provencal and French forms – added to the poetic mix, creating a vast community of poets who recited their works in various forums. In the theater, their verse often preceded Shakespeare and Marlowe dramas – a practice followed nearly four centuries later by many of San Francisco’s 1960s rock musicians, who preceded their concerts with readings from Beat poets.

The socially open Elizabethan era enabled poets to write about humanistic as well as religious subjects. The dramatic rise in academic study and literacy during the late 16th century created large audiences for the new poetry, which was also introduced into the educational system. In many ways, the Elizabethan era more closely resembled the expressionism of the Ancient Greeks than the Sicilian and Italian Renaissance schools from which it derived its base poetry.

Metaphysical poets

A century after the height of the Elizabethan era, a subtler, provocative lyric poetry movement crept through an English literary countryside that sought greater depth in its verse. The metaphysical poets defined and compared their subjects through nature, philosophy, love, and musings about the hereafter – a great departure from the primarily religious poetry that had immediately followed the wane of the Elizabethan era. Poets shared an interest in metaphysical subjects and practiced similar means of investigating them.

Beginning with John Dryden, the metaphysical movement was a loosely woven string of poetic works that continued through the often-bellicose 18th century, and concluded when William Blake bridged the gap between metaphysical and romantic poetry. The poets sought to minimize their place within the poem and to look beyond the obvious – a style that greatly informed American transcendentalism and the Romantics who followed. Among the greatest adherents were Samuel Cowley, John Donne, George Herbert, Andrew Marvell, Abraham Cowley, Henry Vaughan, George Chapman, Edward Herbert, and Katherine Philips.

The Romantic movement lasted about 25 years, until Lord Byron’s death in 1824, and was one of the greatest movements in literary history.

|

John Dryden epitomized the metaphysical movement, which looked beyond the obvious and minimized the author’s place within the poem.

|

Romantic poets

The third of England’s "big three" movements completed a three-century period during which the British Isles took the Western poetic mantle from Italy and molded the forms, styles, and poems that fill school classrooms to this day. The Romantic period, or Romanticism, is regarded as one of the greatest and most illustrious movements in literary history, which is all the more amazing considering that it primarily consisted of just seven poets and lasted approximately 25 years – from William Blake’s rise in the late 1790s to Lord Byron’s death in 1824.

Ironically, the poets held distinctly different religious beliefs and led divergent lifestyles. Blake was a Christian who followed the teachings of Emmanuel Swedenbourg (who also influenced Goethe). Wordsworth was a naturalist, Byron urbane, Keats a free spirit, Shelley an atheist, and Coleridge a card-carrying member of the Church of England.

The romantics made nature even more central to their work than the metaphysical poets, treating it as an elusive metaphor in their work. They sought a freer, more personal expression of passion, pathos, and personal feelings, and challenged their readers to open their minds and imaginations. Through their voluminous output, the romantics’ message was clear: life is centered in the heart, and the relationships we build with nature and others through our hearts defines our lives. They anticipated and planted the seeds for free verse, transcendentalism, the Beat movement, and countless other artistic, musical, and poetic expressions.

The Romantic movement would have likely extended further into the 19th century, but the premature deaths of the younger poets, followed in 1832 by the death of their elderly German admirer, Goethe, brought the period to an end.

American Transcendentalists (1836-1860)

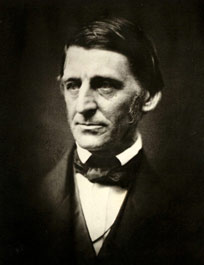

Of all the great communities and movements, the American Transcendentalists might be the first to have an intentional, chronicled starting date: September 8, 1836, when a group of prominent New England intellectuals led by poet-philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson met at the Transcendental Club in Boston. They gathered to discuss Emerson’s essay, "Nature" and developed "The American Soul," which stated, "We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds ... A nation of men will for the first time exist, because each believes himself inspired by the Divine Soul which also inspires all men."

The Transcendentalist Movement began when New England intellectuals gathered to discuss Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay, "Nature."

|

Many literary giants, including Louisa May Alcott, considered themselves Transcendentalists.

|

A number of great authors, poets, artists, social leaders, and intellectuals called themselves Transcendentalists. They included Emerson, Bronson Alcott, Louisa May Alcott, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, Orestes Brownson, William Ellery Channing, Sophia Peabody, and her husband, Nathaniel Hawthorne.

The Beat movement (1948-1963)

It only lasted 15 years and was known by the masses only in the last six, but the combination of disenfranchisement, wanderlust, and creative expression that inflicted a handful of New York and San Francisco students and young intellectuals resulted in the most influential movement of the past 100 years – the Beat movement.

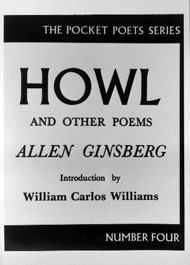

The Beats formed from a wide variety of characters and interests, but were linked by a common thread: a desire to live life as they defined it. The mixture of academia, be-bop jazz, the liberating free verse of William Carlos Williams, and the influence of budding author Jack Kerouac (who coined the term "Beat Generation" in 1948 at a meeting with Allen Ginsberg, Herbert Huncke, and William S. Burroughs) inspired a young Ginsberg to change everything he’d learned about poetry. He wrote throughout the early 1950s in a narrative free verse, joined by the young Gregory Corso and Peter Orlovsky, and the older Burroughs, who, like Kerouac, opted for fiction – though Kerouac wrote beautiful poetry that has been read and appreciated over the past two decades.

By the mid-1950s, the Beats’ mixture of free-expression jazz and socially informed free verse poetry became the anthem for a generation of Greenwich Village youth seeking greater spiritual meaning through visceral experiences and the laying down – or trampling – of their parents’ strict, Depression and World War II-fed mores.

By the time of the Six Gallery reading, San Francisco was host to a burgeoning Beat community that included poets Gary Snyder, Michael McClure, Philip LaMantia, and three older influences: Kenneth Rexroth, Lew Welch, and Philip Whalen. In 1947, Rexroth launched the San Francisco Renaissance, a loose poetic movement including he, Whalen, Kenneth Patchen, and William Everson. It directly fed the San Francisco Beats, as did the Black Mountain Poets that included Robert Duncan and Denise Levertov. Another major contributor was former New York poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who owned and operated City Lights bookstore, which in the 1950s sold books that were banned by the U.S. Justice Department. He published Howl, thus creating a legacy as the greatest publisher and distributor of Beat literature.