Lost Shadows

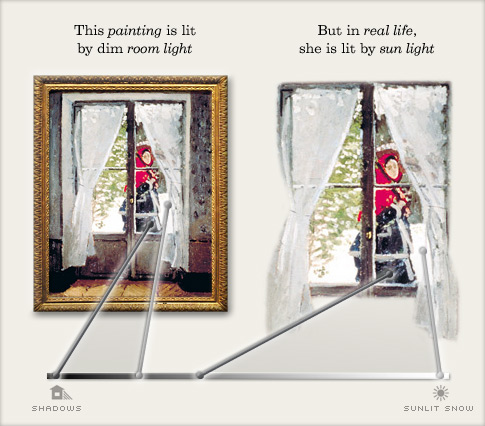

Historically, it has been a challenge for artists to capture the varying luminance of the outside world on canvas. Our eyes can see enormous ranges in brightness, from the dark shadows to bright sunlight. But pigments have a limited range of reflectance.

Medieval paintings appear flat because medieval artists used a limited range of luminance. Over the years, Madonna has traditionally been portrayed with a dark blue cloak with a red lining or undergown. Medieval artists’ inability to show shadows in the dark cloak arose from their difficulty in achieving a range of luminance.

Madonna and Child, André Berlinghiero, c. 1230. The strong emotions, angular face and furrowed brows are typical of this Byzantine panel painting. Madonna’s robe is dark and seems flat because you can barely see the shadows signifying the folds, which are only slightly darker than the rest of her robe. The gold background also flattens space, which is one reason why Cennini and Alberti were praised painters who could imitate the effect of gold with shades of yellow paints.

In the Madonnas shown here, the lighter robes of the other figures and of the Christ Child do show folds that are significantly darker than the rest of the robes. The lighter robes depict a much broader range of contrast than Madonna’s darker robe. The only clear hints as to the folding of her robe are the undulations of its gold edging.

The Madonna in Majesty, Cimabue, c. 1285-6. Madonna’s dark robe has less luminance contrast than her red gown or the Christ Child’s lighter robes.

In the painting at left, Cimabue (c. 1240-c. 1302) overlays both robes with gold highlighting (chrysography). The gold conveys grandeur and otherworldliness, but it is also a mechanism for indicating the folds of the fabric, which are not well delineated by the small luminance contrast the artist gave the darker color.

The solution to this problem was the invention of chiaroscuro. In art, chiaroscuro is the distribution and contrast of light and shade in a painting or drawing, whether in monochrome or in color. The term is derived from the Italian chiaro (“light”) and oscuro (“dark”) and generally refers to a technique that contrasts bright illumination with areas of dense shadow. The skillful use of light and shade (sometimes called values) for dramatic effect is a particular feature in the works of such 16th century Renaissance masters as Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael (Raffaello Sanzi, 1483-1520) and such 17th century Baroque masters as Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi, 1571-1610), Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and Georges de La Tour (1593-1652). Chiaroscuro is seldom found in pre-Renaissance or in non-Western art.